BRAND VALUATION BEST PRACTICE APPROACH

Jan Lindemann

Out of current brand valuation theory and practice, some consensus on brand valuation emerges. This has been distilled into a tested and recommended brand valuation framework and will be described. The review of the different approaches to brand valuation demonstrates that the approach needs to integrate marketing and financial analyses without sacrificing one to the other. In line with corporate finance theory, as well as capital market and industry practice, the main valuation approach should be a NPV of future expected brand earnings. The valuation approach needs to focus on the specific value creation of the brand to be assessed. The use of comparables including royalties, as well as transactions, should be confined to cross-check analyses and not constitute the main approach. Cost approaches are only appropriate in situations where the brand has not yet been used, or has had no measurable impact on the market. This section develops, out of empirical experience and the review of the currently used methods, a best-practice approach to brand valuation. The recommended valuation approach should comprise five key steps as shown in Figure 7.1.

Step 1: Market segmentation

Most brands operate in more than one market segment which is reflected in their value creation. For example brands such as GE, Siemens, and Samsung sell a wide range of products to very different customer groups. The Samsung brand sells TVs to consumer markets around the world as well as memory chips to computer and mobile phone manufacturers. The same brand affects the different customer groups to a different degree with a different financial result. For example the Samsung brand may have a higher impact on the purchase decision of a television but the impact of the Samsung brand

FIGURE 7.1 Brand valuation methodology

on the purchase of semiconductors may result in a higher financial gain. This is crucial information for managing the brand as it impacts positioning, communications, and investments.

It is therefore important to understand the variety of market segments a brand operates in and how deep it has penetrated the different segments. Market segment is defined by two key characteristics. First, the segment needs to be distinguished from other segments according to clear and evident criteria that affect the purchase decisions of consumers in that segment. Second, the behavior and perception pattern of consumers in the segment need to be sufficiently homogenous. Some segmentation approaches are relatively easily defined and deliver clearly distinctive segments. For examples segmentations by industry sector, product, geography, or demographics will provide clearly identifiable groups. Segmentations according to purchase behaviors are less clear-cut but still relatively easily defined by frequency, volume, price, and seasonality. Attitudinal segmentations are in particular important for brands as they refer to perception of needs, relevance, values, image attributes, satisfaction, and recommendation. An attitudinal segmentation is particularly important for brand management purposes as it allows the brand positioning, messaging, and investments to be focused on the most relevant and financially rewarding areas. The key business objective of branding is to influence peoples’ minds and attitudes in a way that makes them buy more of a company’s product at a higher price again and again. Influencing attitudes leads to desired behaviors and financial outcomes.

Attitudinal segmentations rely, however, on the quality of the survey questions and can differ significantly according to the questions asked. In most cases the segmentation will combine several approaches such as product, geography, consumer behavior, and attitude. The purpose of the segmentation is to identify brand relevant segments for which sufficient marketing and financial data are available. The segments need to be materially and strategically relevant with respect to profitability and actionability. The segmentation will also make the valuation more accurate. However, the approach to segmentation should be commercially pragmatic and fit with the purpose of the valuation. In most cases a valuation for management and controlling purposes will be more detailed as it needs to link specific actions and investments with specific market segments. Accounting valuations are less “granular” as they focus on the overall value of the brand. Once the appropriate segmentation is in place the valuation of the brand is conducted in each of the identified segments. The sum of the segment valuations represents the overall value of the brand.

Step 2: Financial analysis

The brand operates on the “outside” of the business by attracting and securing customer demand. Customer demand converts into purchase price, volume, and frequency. The financial forecast assesses the revenue that the brand is expected to generate in the future. The purpose of a brand valuation is to value the useful life of the brand asset. If the brand and the underlying business are a going concern without any current signs or intentions of folding then the useful life time is considered unlimited. If the useful life of the brand is contractually limited due to a licensing agreement then the forecast has to focus on the time period stipulated in the contractual agreements. If the licensing agreement includes an option of renewal then this can be taken into consideration in the forecast. In most cases the brand is valued as a going concern which means the valuation will cover all future expected cash flows attributable to the brand.

In order to prepare the forecast the first step is to identify historic and current revenues that have been generated by the brand. Then the costs and associated capital required to deliver these revenues needs to be identified. For companies that use only one brand, such as IBM and Samsung, the brand and company’s financial information is identical because all company assets support the sale and delivery of the branded offer. For companies that use several brands the financial data need to be identified for each specific brand. In cases where the brand and the underlying operations are clearly separated this information can be obtained at least at cost level. However, in some cases the operations of several brands are so closely intertwined that it is difficult to separate cost and capital employed by brand. In such cases cost and capital employed need to be allocated based on group or consolidated data. Such allocations are ideally based on detailed discussions with management and the finance department. Once the allocation assumptions are identified and agreed brand specific financial data can be obtained. Based on the historical and current financial and brand data a brand specific forecast is prepared. While current and historical analyses provide some guidance the main focus has to be on the expected performance of the brand. Based on a thorough

understanding of the macro- and micro-economic conditions in which the brand operates the forecast needs to take into consideration customer needs and behaviors, the brand’s positioning in the market place, segment and GDP growth rates, disposable income or budgets, the competitive environment, past and planned brand investments, product innovations, changes in distribution, operating margins, and investment requirements. This is a complex process and requires detailed understanding of the brand and its underlying business. The forecast should capture the demand the brand is expected to generate given the macro-economic outlook. The macro-economic outlook is set by GDP growth rates, inflation rates, and expected consumer spending within the respective category. Within this framework the brand’s specific revenue generating capability needs to be assessed according to brand perception and behavioral data. Starting points are historic revenues and the short-term revenue in the budget if available. Volume and value market share as well as pricing and purchase frequency data form the basis for the revenue forecast. Financial forecasting is a combination of art and science embedded in a deep understanding of the brand and its markets. Despite the technical analysis and data input the forecast needs to be assessed according to the soundness not only of the input data but also the overall result. An overly optimistic forecast in sales increases and unrealistic assumptions can render the whole valuation meaningless. It is always important to cross-check the overall result of the revenue forecast with historical performance, competitors, and the market.

The expected demand from the brand is represented by sales price and volume translated into a revenue forecast for the brand. From the forecast revenues all necessary operating costs are subtracted to derive the EBITA. This figure includes the depreciation which is assumed to represent the annual average spend for required capital investments but excludes amortization which represents a return of intangible assets. From the EBITA required taxes and a charge for the capital employed are deducted. Capital employed is the operationally required net fixed assets plus net working capital. The charge for the capital employed represents the adequate return required for the use of the tangible assets necessary to deliver the revenues of the brand. The companies’ weighted cost of capital (WACC) is assumed to represent an adequate return on the capital employed as it is the return capital provides (debt and equity) required to provide funds. TheWACC concept and calculation is firmly established within the business and finance community and used within most companies. After subtracting taxes and a charge for the capital employed the remaining profit is called intangible earnings as it represents the earnings attributable to the intangible assets. The concept of intangible earnings is similar to economic value added and in particular suitable for valuing bundles of assets with different returns. The result of the financial analysis is a forecast of intangible earnings derived from revenues created by the brand. The forecast is based on a deep understanding of the brand and its market. The forecasts should be based on sound analyses and assumptions. While the past is not guidance for the future, historical analysis should be used to cross-check and verify assumptions. As with all forecasting assumptions these should be transparent, kept as simple as possible, and as complex as necessary. There are good statistical modeling tools available that use a vast array of data to build future scenarios. While these are helpful, they should not be used to build impenetrable black-box models or hide assumptions in overly complex calculations. As most of these models are built on the analysis of the correlations and regressions of historical and current data they tend to predict within existing systems. This can be useful for short-term trends but is very hard to apply for long-term horizons. As most forecast periods stretch between 3 and 10 years there is a need to develop a strategic long-term view – the longer the forecast horizon the higher the margin for error. In most cases the valuation consists of two forecast periods. An explicit and detailed forecast which is, on average, for a 5-year period and a forecast of the cash flow into perpetuity which is mostly the previous year’s cash flow multiplied by a long-term growth rate. Although most effort is made in preparing the explicit forecast period the value impact of the perpetuity cash flow is much higher and can easily amount to twothirds of the overall value. Forecasting is not an exact science as many economic and financial experts experienced in the 2008/9 recession. More data does not automatically translate into more insights and better forecasts. Data modeling and judgment need to feed off each other to deliver the best possible forecast. The forecast needs to represent the best possible view based on the available data and information. The complexity and detail of the forecast will depend on the purpose and the time frame of the valuation. Brand valuations for management purposes will need much more detailed insights and understanding of causal relationships as they are supposed to provide a solid base for the strategic management of the brand. Valuations for financial purposes will focus more on the relative soundness of the financial data.

The financial analysis is a crucial part of brand valuation and needs to be conducted with the same detail and diligence as the marketing analyses. It is important that the financial analysis includes and integrates the available marketing data in order to avoid the financial analysis being conducted separately. The purpose of the financial analysis is to provide a forecast of the intangible earnings.

Step 3: Brand impact

The intangible earnings represent the return of all intangible assets of the branded business. For valuing the brand the brand-specific earnings need to be identified.

That means the intangible earnings need to be split between brand earnings and other intangible earnings. This approach is therefore called the profit-split approach. The brand specific earnings can be identified in different ways. The accounting approach is to assume fictitious returns for the different assets including the brand. These returns are derived from analyzing comparable companies and assets and then deriving a respective return. Such an approach however, relies on the quality of the comparisons made. As mentioned previously in the case of brands comparability is difficult as by definition brands have to be different to create value. The Coca-Cola/Pepsi-Cola comparison makes this evident. In addition such an approach does not identify the brand specific value creating factors. It provides only a number but not a solid economic rationale for the validity of this number. A better and much more suitable approach is to assess how the brand creates revenues relative to the other intangible assets of the business. The brand creates revenues through price, volume, and frequency of purchase. To deliver these branded revenues operating costs and capital are required. They are remunerated according to the cost and capital structure of the underlying business which is reflected in the intangible earnings calculation. However, while the reported financial data provide operating costs, taxes, and capital employed, the WACC and other relevant data do not provide the return of specific intangibles let alone the brand. For that reason the brand-specific earnings need to be separated from the earnings of all intangibles. This approach assesses the brand in its context with other intangibles. By looking at the demand and subsequent revenue generation of the brand its specific contribution to the profit generation of the underlying business can be assessed. The starting point is to identify the way brands create demand and subsequently revenues. This requires analysis and dissection of the purchase decision of customers and consumers. Consumers as well as professional buyers base their purchase decision on a wide range of perceptions and emotions.1 Modern research techniques can provide a detailed understanding of purchase motives, purchase funnels and how these are impacted by customer perceptions. As discussed in Chapter 1 brands are a combination of promises and experiences that create a certain perception about a company’s products and services. As this perception impacts the purchase by customers it represents a good measure for the relative influence the of brand. A customer makes a purchase decision on a variety of criteria. This includes price and availability as well as functional and emotional benefits. The bundle of these purchase drivers leads to a transaction between customers and suppliers. As in nearly all purchase decisions there is a choice between competing products and services. Most brands in the same category will offer similar tangible benefits and a unique mix of intangible benefits. Some of the intangible benefits can also be similar but the overall mix of brand perceptions will be different. For assessing how customers perceive a brand and how this perception then guides their purchase decision appropriate market research data need to be prepared and analyzed. Most companies will have a variety of surveys and research on this subject. The research methodologies can be qualitative and quantitative. Qualitative research has the advantage of probing deeper and being able to provide more detail about brand perception and purchase behavior. Qualitative research comprises of in-depth one-to-one or group interviews as well as focus groups. Through their interactive nature qualitative research can provide unique insights and understanding of brand perceptions and purchase decisions. Observation research is another way of analyzing and understanding shopping behavior through detailed observations and in some cases subsequent interviews. Although qualitative research is most insightful in understanding perceptions and purchase behavior it is limited by the number of interviewees and therefore its statistical relevance. Quantitative research data are required to provide a sufficient number of interviews in order to provide statistically reliable data. Most of the leading market research firms run standardized panel surveys which provide some basic quantitative research.

In addition, most research firms provide tailored surveys to meet specific requirements. Most firms offer surveys that include all main input data such as awareness, relevance, consideration, image attributes, and purchase intention. However, due to their standardization and the increasing use of online surveys the depth of this type of research is limited due to the selection of the questions included in the questionnaire. The quality of the research becomes apparent when purchase drivers and brand perceptions are linked through statistical analyses and modeling. It is not unusual that even tailored and assignment specific research surveys prepared by established market research firms deliver only a limited number of purchase drivers due to overlapping questions and lack of relevant questions. This can impair the result and its usefulness for management. Market research is a topic in its own rights and this book does not intend to provide a comprehensive overview and critique of different market research approaches. It is, however, important to understand the quality of the data input in order to design a suitable model to explain the impact of brands on purchase decisions and value creation. Ideally, the market research is designed specifically to identify and understand the purchase drivers and how they are impacted by the brand. However, due to the relatively high costs of these surveys many companies will want to make use of existing research data. In most cases it is possible to find a way of incorporating the data into a suitable model.

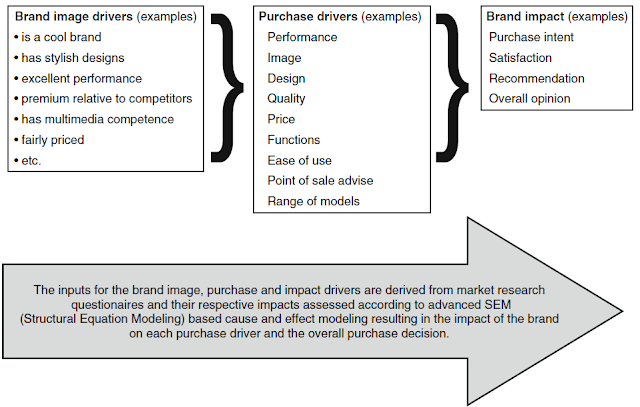

The first step in assessing the impact of the brand on customers’ purchase decisions and revenues is to identify the reasons why customers chose to consider and buy a specific brand. There will be functional or tangible and emotional or intangible benefits that drive the purchase. These benefits are at different degrees represented by the brand and its perceptions. Some purchase drivers are entirely dependent on brand perception. They comprise benefits that are based on perception without close comparison or testing of competing offers. These intangible benefits fall into two categories. The first category comprises benefits that are purely emotional and cannot be materially tested and compared. They include perceptions of emotions such as friendliness, approachability, care, status, coolness, stylishness, and happiness (see Figure 7.2).

These perceptions cannot exist without the brand as they are not attached to tangible or testable functionality of the product. Then there are perceptions of functional benefits that can be tested and compared but are mostly assumed in a purchase decision. This is either due to the fact that testing and comparing these benefits is technically difficult and time-consuming or the lack of interest in delving into the detail of

FIGURE 7.2 Brand impact assessment (example mobile handset brand) 1

the offer. For example in the purchase of a TV set consumers will rely on brand perception regarding quality, functionality, reliability, and durability because they will have limited or no means to test and compare these product features. In some cases publicly available test reports will function as a proxy for performing customized comparisons. In many cases a wide range of functional and technical benefits will be included in customers’ brand perception. Product quality is a key feature for most products and most brands will include some level of quality perception. The alignment of product features and quality in most categories has made it hard to distinguish products on these levels. In the case of flat panel TVs there are only a small number of suppliers of the screen panels which constitute a major component of the product. As a result, a Sony branded TV will have a screen that is made by a joint venture with Samsung although both brands compete in the same product category. Most consumers will not be aware of this and will regard the brands’ product as distinctive and separate offers. Similar examples can be found in the car industry: VW’s Touareg and Porsche’s Cayenne are built on the same platforms and share most components. Although the Cayenne comes with a more powerful engine option, most reviews could not find significant differences between the two vehicles. Even visually both cars are very similar. The biggest difference is the price as at comparable engine levels the Porsche is about 60 percent more expensive than the VW Touareg. These examples illustrate the fact that many functional and tangible benefits, such as quality, are significantly carried by brand perceptions. Without the brand the quality promise of most products and services would not be credible. The impact of brand perceptions on functional or tangible benefits is very important for B2B brands where emotional benefits can be relevant but not to the same degree as for consumer brands. Professional service brands such as IBM, SAP, PricewaterhouseCoopers, Goldman Sachs, and McKinsey will provide a wide range of functional benefits that are difficult to test and compare. They will offer professional expertise, customer service, efficient project management, and performance improvements which rely strongly on their specific brand perceptions. In some cases, functional benefits can be a brand’s main component. The Volvo brand has for decades focused on safety although most comparable cars offered similar safety features and performance. Functional benefits can therefore be very dependent on the brand’s perception as the actual differentiation in the delivery and result of the functional benefit is often very similar and hard to distinguish. On the other hand, there are functional benefits that are not dependent on brand perceptions but deliver clear tangible results such as drug or software patents. In the case of professional service firms, specific individuals can have a strong impact on customers’ purchase decisions as clients follow them when they leave the firm.

Once the key purchase drivers have been identified they need to be assessed according to their relative importance or impact on customers’ purchase decisions. This can be achieved through applying statistical modeling techniques such as structural equation modeling (SEM). Through the statistical analysis process the research results can be translated into single clearly defined purchase drivers. Once the purchase drivers and their relative importance have been assessed, the impact of the brand on the purchase drivers can be determined. From the research the brand perceptions are identified and then assessed according to their impact on the purchase drivers. It is important to analyze the impact of the brand on the purchase driver and not as a separate purchase driver, as the brand represents all perceptions of a company’s products and services. As such the brand is closely interwoven with the other tangible and intangible aspects of the offer. In the cases of functional or tangible product drivers it is the combination of brand perception and actual product delivery that drives the purchase. In

FIGURE 7.3 Brand impact assessment (example mobile handset brand) 2

the case of quality and functionality as a purchase driver some aspects can be and are assessed by customers and some not. However, in most situations product quality will be part of brand perception.

Brand impact is measured through a two-tier approach. First, the percentage impact of each purchase driver is assessed (see Figure 7.3). Once the percentage impact of each purchase driver is determined the impact of the brand on each driver is assessed. The result is the brand impact which is the percentage impact brand perceptions have on each of the purchase drivers. These are then multiplied by the percentage impact of the purchase drivers to deriver the overall brand impact. Brand impact varies by driver and brand. The higher the brand impact the higher the dependence of the purchase on the brand. Consumer and luxury goods have an average brand impact of 60–90 percent as most purchase drivers are heavily impacted by brand perception. Coca-Cola, Louis Vuitton, and Nivea are purchased because of the brand perceptions delivered by the underlying product. The Coca-Cola brand’s key perceptions are refreshment, American heritage, the original and genuine cola, and fun and enjoyment. Although the brand is supported by a strong global distribution network its success is driven by consumer pull. The Louis Vuitton brand’s perception comprises of style, status, luxury, French sophistication, timeless chic, and design. Despite a strong logo display on its core product line up Louis Vuitton has assumed a position of

FIGURE 7.4 Brand impact average by category

classic and timeless chic. Although the products are of high quality and meticulously manufactured they would lose their customer attraction without the LV brand. Nivea’s brand perceptions are wholesomeness, cleanliness, caring as well as credibility, and genuineness built by its long history. The products are well-made but would be indistinguishable without the Nivea brand. Although all these brands have a physical delivery it is the perceptions that consumers have about these brands that drive their purchase. The products are of high quality, within their segments, but the consumer demand for these products is created through emotional brand perceptions. The brand impact is therefore very high and dominates the purchase decision. The underlying product, service and distribution support the creation and maintenance of these brand perceptions. There are categories where the range of the brand impact can be significantly wider (see Figure 7.4). These include consumer durables such as cars and consumer electronics. Here brand impact can vary between 45 and 70 percent.

At the high end are brands such as Apple, Blackberry, BMW, Audi, Porsche, and Mercedes-Benz where despite the equivalent technology involved brand perceptions dominate the purchase. Without Porsche’s brand perception the company’s cars would still be well-designed, styled, and engineered cars, but customers would lack the prestige, status, and sophistication that these brands represent. In these categories there are also brands where the tangible functional aspects are very important and the brand perception is not about emotional values but represents functional benefits such as quality and durability. Brands in this category include Nissan and Sharp.

Most B2B brands have a brand impact of between 25 and 50 percent. Professional service firms are at the higher end of the scale as the actual performance of the deliverable is hard to measure. The impact on the client of a piece of consulting advice from McKinsey or a software solution from SAP depends on their execution and implementation. These firms live strongly on their reputation and the widely quoted phrase “nobody has been fired for hiring IBM” illustrates the impact brand perceptions have in choosing these suppliers. Low-brand impacts are found in commodity and special industries where nonbrand drivers dominate. An example is retail petrol where price and location are the key drivers and the brand impact is below 25 percent. However, in retail lubricants brands can have a very high impact similar to the consumer brands. Brands such as Mobil and Castrol have brand impacts at the high end of the consumer brand range. As noted earlier, brand impact can vary significantly by customer segment, product line, or geography. Toyota and Honda have a higher brand impact in Asia and North America than in Europe where they are predominantly a functional purchase with little or no emotional benefits.

As brand impact measures the relative contribution the brand makes to the overall purchase, it is the most suitable figure to use for determining brand-specific earnings. Brand earnings are calculated by multiplying the intangible earnings by the brand impact percentage. The brand impact analysis provides the most suitable way of assessing brand earnings as it is based on the brand’s specific impact on customer purchase decisions and revenue generation.

The brand impact analysis delivers a brand specific contribution to the underlying business. As such it values the brand in a specific and existing context of other intangible and tangible assets. If these circumstances change the brand impact analysis needs to be adjusted accordingly. This would be the case if the brand were taken into a different business context either through sale or extension into new or unrelated areas. For example, in the UK, theWoolworth’s brand was sold in June 2009 to a pure online retailer after the operations collapsed and the company had to file for bankruptcy.2 The new online operations are not yet established but its brand impact will change as there is no store network for brand promotion. That will potentially mean that the brand impact will increase as it will be the Woolworth’s brand that will bring customers to the website. It may also make the brand more valuable as it is driving a profitable business model.

The brand impact analysis also provides a key management tool for understanding and managing the brand value creation. Through a detailed understanding of purchase drivers and how they are impacted by brand perceptions, marketing strategies and investments can be optimized according to brand impact. It also provides the impact of each single brand element and the opportunity to design the best fit with the respective customer groups.

Step 4: Discount rate

Once the brand earnings forecast has been completed the appropriate discount rate needs to be determined to calculate the NPV of the brand earnings which represents the value of the brand. According to the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), the discount rate represents the relationship between risk and expected return. Potential investors need to be compensated in two ways: time value of money and risk. The time value of money is represented by the risk-free rate that compensates for investing money over a period of time. The risk-free rate is best represented by government bond yields. The discount rate needs to reflect the risk of the expected brand earnings relative to the risk-free rate. A high discount rate indicates a high level of risk and therefore a lower expectation that the brand earnings will be delivered as projected. A high discount rate results in a lower NPV. A low discount rate represents a low level of risk and thus a high expectation of achieving these earnings. A low discount rate results in a higher NPV. The discount rate needs to reflect the risk profile of the brand or the likelihood that the brand will deliver the expected earnings. For business valuations according to CAPM the discount rate is represented by a company’s weighted cost of capital (WACC). This calculation represents the weighted return to all capital providers according to their contribution in financing the business. The two principal types of capital are debt and equity. The “cost of equity” is the risk-free rate plus the equity risk premium adjusted for the company specific beta. The equity risk premium represents the additional return investors require in order to invest in the more uncertain and therefore riskier return from stocks. The equity risk premium differs according to market, whether it is historical or prospective and whether it is based on arithmetic or geometric averages. However, most practitioners use a premium of between 3.5 percent and 7 percent. The premium is then adjusted for the volatility of a company’s stock versus the overall market measured by the beta. The beta of the market is one. A stock that is more volatile than the market has a beta above one. Many technology businesses fall into this category. A stock that is less volatile in its performance versus the stock market has a beta below one. Many consumer staple companies and utilities fall into this category. The cost of debt is the effective rate that a company pays on its debt. Since interest expense is tax deductable, the after-tax rate is most often used. The cost of debt and cost of equity are weighted according to the structure of the capital of the business. The problem with using theWACC for valuing brands is that it is based on the assessment of all business assets combined. The risk of the brand is integrated with that of the other business assets. It is therefore argued by some brand valuation experts that theWACC is too broad for valuing the brand as it does not provide an asset specific risk. In principle this is correct as different assets have different risk profiles. For example, the economic return from R&D assets, such as new patents and technologies, has a much more uncertain outcome than the return from established brands. It is therefore fair to expect that their respective discount rates would differ. This is the reason why many brand specific valuation approaches use an alternative risk assessment that is a hybrid of CAPM and brand specific factor scoring models. As with the CAPM approach the starting point is the risk free rate. To the risk free rate they add a premium that is not driven by the capital structure of the underlying business but by an assessment of the strength of the brand and its market. The brand’s risk profile is determined through a set of metrics that look at the brand’s competitive position with in its markets and the condition of the markets the brand operates in. These metrics are converted through a distribution curve or logarithm into a brand specific discount rate. The metrics combine macro-economic data, market research data, and assessments of brand management. The data inputs include GDP growth rates, inflation rate, market share, market share growth rates, market ranking, price differentials, customer loyalty, satisfaction and advocacy, consumer perception of brand values, differentiation, relevance, product innovation, marketing spend, advertising effectiveness, consistency of brand communications, and legal IP management. The data are grouped into different assessment topics – some data are selected to be converted into a scoring framework. The alternative brand risk assessment models look at a set of brand metrics that are useful in evaluating the sustainability of the brand’s ability to generate future cash flows. As such they are very valuable analyses and can be used within a brand management framework. The alternative brand strength or risk assessment models are however the most challenged elements of many brand valuation methodologies. While CAPM theory and portfolio theory have emerged from decades of corporate finance and practice based on market data dating back to the 1920s, the information and research available on brands is substantially thinner and much patchier. It is therefore difficult to replicate a comparable level of data depth and quality. The other issue with the alternative risk assessment approaches is the actual use and validity of converting a wide range of data into a valid discount rate.

Many approaches have to rely on set of assumptions that have and cannot be verified due to the complex nature of brands. While the profit split to derive brand earnings is based on accepted and tested business concepts and practice it is harder to find a marketing and financial consensus around the alternative discount rate assessment. There are many companies who operate only under one brand or where one brand dominates the company’s business such as IBM, Nokia, Starbucks, McDonald’s, Apple, BMW, Mercedes-Benz, and HP. The WACC of these companies fairly reflects the risk of their brands in their current use because the risks of all assets are intertwined. The analysis of companies operating under a master brand suggests that there is little evidence for a meaningful split between brand and business discount rate. It is therefore more robust and reliable to use the WACC for discounting brand earnings.

Determining a suitable discount rate is often the most difficult and uncertain part of a DCF valuation. This is made worse by the fact that the NPV is very sensitive to the choice of discount rate as a small change in the discount rate causes a large change in the overall value.

In the end the discount rate needs to be credible to a financial audience. The theory for a pure brand-specific discount rate independent of the CAPM framework is interesting but not practical and with the current data availability difficult to implement. This is demonstrated by companies that operate under only one “master brand.” It is therefore advisable to use the WACC as a brand discount rate in situations where the brand is used in all or the main cash flow generating activities of the business. In cases where the brand is part of a large portfolio and does not represent the majority of the business, the WACC should be adjusted according to a range of betas available for the respective industry. The discount rate is used to calculate the net present value (NPV) of the expected future brand earnings.

Step 5: Calculating brand value

The value of the brand is the sum of the NPVs of the forecast brand earnings of the identified segments in which the brand is valued. The value consists of two sets of discounted brand earnings. The first set is the detailed forecast as discussed in the previous section. The detailed forecast normally covers a period of five years, though longer time-frames are also used. If a brand is valued as an on-going concern its value creation will extend beyond the explicit forecast period. The second set is the terminal value which represents the brand earnings beyond the explicit forecast into perpetuity. The brand earning of the last year of the explicit forecast period from the basis for the terminal value calculation. A constant growth rate (e.g. long-term nominal GDP growth rate) is used to grow these brand earnings into perpetuity. The long-term growth rate needs to represent the growth potential of the brand’s earnings into perpetuity. The selection of the brand earnings forecast for the terminal value calculation is very important as in many valuations the terminal value exceeds the NPV of the explicit forecast. For that reason the brand earnings number used for the terminal value should reflect the long-term ability of the brand to generate these cash flows. This is the reason why in some cases the earnings figure for the terminal value calculation is adjusted. The terminal brand value is then calculated by dividing the final brand’s earnings beyond the forecast period by the discount rate minus the long-term growth rate. The brand value is then the sum of the NPV of the explicit forecast and the terminal value. The valuation is different for situations in which the time for the use of the brand is limited. This would be the case for a licensing agreement with an agreed time limit. Under such circumstances brand earnings are forecast only for the period of the licensing agreement. An exemplary brand value calculation for a fictitious mobile handset brand is shown in Table 7.1.

The outlined valuation approach aligns the value of brands with established and widely used valuation approaches. Through brand valuation brands become comparable to other business assets as well as the overall company value.

CONCLUSION

It is important to bear in mind that a valuation approach delivers a framework but not an automated answer. Brand valuation is a derivative of business valuation and therefore, faces similar issues. In the debate about valuing brands the precision or lack of precision is still a major point of discussion. There are different approaches and views on what is the right or correct way of valuing brands. The five-step model outlined a framework that provides the most robust and reliable results. However, the model is only one part of the equation. A fair and robust valuation requires the right data inputs and assumptions. As with a DCF model or other valuation approaches the same model does not provide the same value. All valuation frameworks and in particular the ones that are based on forecasts carry a significant level of uncertainty. In spite of the availability of a wide range of marketing and financial data a valuation is always at a point in time, and as such subject to change.

As outlined in Chapter 2 the valuation of brands is a complex affair as it requires a detailed understanding of marketing and finance. The question that arises is: Whybother with all the complications of valuing brands? The answer is relatively simple. With the established understanding that brands are key corporate assets the need has emerged for the economic valuation of brands for a wide range of management and transaction requirements. The following chapters will deal in detail with the diverse use of brand valuation in management, commerce, and finance.

TABLE 7.1 Brand valuation of mobile handset brand

NOTES

1. See Jacob Jacoby, 2001; Max H. Bazerman, 2001; Khalid Dubas, M. Dubas and Petur Jonsson, 2005.

2. Simon Bowers, 2009.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

D. Aaker, Building Strong Brands (New York: Free Press, 1991a).

D. Aaker, Managing Brand Equity (New York: Free Press, 1991b).

D. Aaker, Building Strong Brands (New York: Free Press, 1996), p. 336.

D. A. Aaker and R. Jacobson, “The Financial Information Content of Perceived Quality,” Journal of Marketing Research, 31, 1994.

D. A. Aaker and R. Jacobson, “The Value Relevance of Brand Attitude in High Technology Markets,” Journal of Marketing Research, 38 (November), 2001, 485–93.

J. W. Alba and J. W. Hutchinson, “Dimensions of Consumer Expertise,” Journal of Consumer Research, 13, 1987, 411–54.

J. W. Alba, J. W. Hutchinson and J. G. Lynch, Memory and Decision Making, in: H. H. Kassarjian and T. S. Robertson (eds) Perspectives in Consumer Behavior, 4th edn (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1991), pp. 1–49.

Ambac Assurance Corporation, “Dunkin’ Brands Securitization Marks Milestone for Innovative Private Equity Financing 2007,” New York, 2007.

American Marketing Association (AMA) 2006, retrieved from: marketingpower.com.

“An Analytic Approach to Balancing Marketing and Branding ROI,” 2007, retrieved from: Enumerys.com.

B. Ataman, H. J. van Heerde and C. F. Mela, “The Long-term Effect of Marketing Strategy on Brand Performance,” 2006, available at: http://www.zibs.com/ techreports/The%20Long-term%20Effect%20of%20Marketing%20Strategy.pdf.

AT&T Inc. Annual Report, 2005.

G. Assmus, J. U. Farley, and D. R. Lehmann, “How Advertising Affects Sales: Meta- Analysis of Econometric Results,” Journal of Marketing Research, 21 (February), 1984, 65–74.

Associated Press, “Honda, Porsche Lead in J. D. Power Quality Study,” June 4, 2008.

L. Austin, “Accounting for Intangible Assets,” University of Auckland Business Review, 9 (1), 2007, 64–5.

N. Bahadur, E. Landry, and S. Treppo, “How to Slim Down a Brand Portfolio,” McLean, VA: Booz Allen, 15 November 2006.

F. Balfour, Fakes! “The Global Counterfeit Business is Out of Control, Targeting Everything from Computer Chips to Life-saving Machines,” BusinessWeek, February 7, 2005, available at: http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/05_06/ b3919001_mz001.htm

BAV Electronics 2006 results, available at: brandassetvaluator.com.au.

M. H. Bazerman, “Is There Help for the Big Ticket Buyer?” Boston, MA: Harvard College, September 17, 2001.

G. Belch and A. Belch, Advertising and Promotion: An Integrated Marketing Communications Perspective (New York: McGraw Hill, 2004).

U. Ben-Zion, “The Investment Aspect of Non-production Expenditures: An Empirical Test,” Journal of Economics and Business, 30 (3), 1978, 224–9.

I. E. Berger and A. A. Mitchell, “The Effect of Advertising on Attitude Accessibility, Attitude Confidence, and the Attitude-behavior Relationship,” Journal of Consumer Research, 16 (December) 1989, 269–79.

R. Berner, “The New Alchemy at Sears,” BusinessWeek, April 16, 2007, 58–60.

R. Berner and D. Kiley, “Global Brands,” BusinessWeek, 5 (12), 2005, 56–63.

Best Global Brand, 2002, BusinessWeek, August 5, 2002.

Best Global Brand, 2008, BusinessWeek, September 29, 2008.

Best Global Brands, 2009, Financial Times, April 29, 2009.

Best Canadian Brands, 2008, available at: Interbrand.com.

“Beyond Petroleum Pays Off For BP,” Environmental Leader, January 15, 2008.

S. Bharadwai, “The Mystery and Motivation of Valuing Brands in M&A,” November 13, 2008, Atlanta, GA: knowledge@emory.

T. Blackett,What is a Brand?Brands and Branding (London: Profile Books, 2003), p.14.

Bloomberg, February 26, 2007, available at: www.bloomberg.com.

Booz & Co., “The Future of Advertising: Implications for Marketing and Media,” February, McLean, VA: Booz Allen, 2006.

S. Bowers, “Woolworth Lives Again as Online Brand,” The Guardian, February 2, 2009.

“Brand Leverage,” McKinsey Quarterly, May 1999, available at: Mckinsey.com.

“Brand Valuation: The Key to Unlock the Benefits from your Brand Asset,” Interbrand, 2008.

Brand Valuation Forum, “10 Principles of Monetary Brand Valuation,” Berlin, June 18, 2008.

BrandZ “Top 100 Most Valuable Global brands 2009,” Millward Brown Optimor, available at: millwardbrown.com.

T. Buerkle, “BMW Wrests Rolls-Royce Name Away From VW,” The New York Times, July 29, 1998.

Burson-Marstellar, “Most Prized Reputation Rankings,” July 17, 2008, available at: http://www.burson-marsteller.com/Innovation_and_insights/blogs_ and_podcasts/BM_Blog/Lists/Posts/Post.aspx?List=75c7a224-05a3-4f25-9ce5-2a90a7c0c761&ID=45.

M. C. Campbell and K. L. Keller, “Brand Familiarity and Advertising Repetition Effects,” Journal of Consumer Research, 3 (September), 2003, 292–304.

P. Chaney, T. Devinney and R. Winer, “The Impact of New Product Introductions on the Market Value of Firms,” Journal of Business, 64, 1991, 573–610.

A. Chaudhuri, “How Brand Reputation Affects the Advertising-brand Equity Link,” Journal of Advertising Research, 42, 2002, 33–43.

S. C. Chu, and H. T. Keh, Brand Value Creation: Analysis of the Interbrand- BusinessWeek Brand Value Rankings (Berlin, Springer Science, 2006).

C. J. Cobb-Walgren, C. A. Ruble and N. Donthu, “Brand Equity, Brand Preference, and Purchase Intent,” Journal of Advertising, 24 (3), 1995, 25–4.

Coca-Cola Company, The, Annual Report 2008, available at: http://www.thecocacolacompany.com/investors/form_10K_2008.html.

Corporate Executive Board, “What companies do best, 2009” BusinessWeek, June 23, 2009.

M. Corstjens and J. Merrihue, “Optimal Marketing,” Harvard Business Review, 81, (October) 2003, 114–21.

M. Deboo, “Ad Metrics and Stock Markets: How to Bridge the Yawning Gap,” Admap, 484, June, 2007, 28–31.

M. G. Dekimpe and D. Hanssens, “The Persistence of Marketing Effects on Sales,” Marketing Science, 14, 1995, 1–21.

N. Delcoure, Corporate Branding and Shareholders’ Wealth (Huntsville, TX: Sam Houston State University, 2008).

DIN ISO Project Brand Valuation, available at: www.din.de. “Do Fundamentals Really Drive the Stock Market?” 2004, available at: Mckinsey.com.

P. Doyle, Value-Based Marketing (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2000).

P. K. Driesen, “BP-Back to Petroleum,” IPA Review, March 2009.

P. F. Drucker,The Practice of Management (Harper & Brothers, New York, 1954) p. 32.

K. Dubas, M. Dubas and P. Jonsson, “Rationality in Consumer Decision Making,” Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Studies, 10, 2, Las Vegas, 2005.

G. Edmondson and D. Welch, “VW Steals a Lead in Luxury,” BusinessWeek, December 6, 2004.

Eisbruck, Jan, “Introduction Royal(ty) Succession: The Evolution of IP-backed Securitisation, Building and Enforcing Intellectual Property Value 2008,” 21, Moody’s Investors Service.

Euromoney Magazine, July 18, 2006.

F. Fehle, S. M. Fournier, T. J. Madden and D. G. T. Shrider, “Brand Value and Asset Pricing,” Quarterly Journal of Finance and Accounting, January 1, 2008.

Financial Times, Invasion, August 2, 2003.

Financial Times, “Global Brands,” FT Special Report, April 29, 2009.

C. Forelle, “Europe’s High Court Tries on a Bunny Suit Made of Chocolate,” WSJ, June 11, 2009.

K. Frieswick, “New Brand Day:Attempts to Gauge the ROI of Advertising Hinge on Determining a Brand’s Overall Value,” November 1 2001, available at: CFO.com.

J. Gerzema, and E. Lebar, Brand Bubble: The Looming Crisis in Brand Value and How to Avoid It (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2008).

“Global 500,” BrandFinance, April 2009, available at: brandfinance.com.

C. Guo, “Co-integration Analysis of the Aggregate Advertising-consumption Relationship,” Journal of the Academy of Business and Economics, February 2003.

J. S. Hillery, “Securitization of Intellectual Property: Recent Trends from the United States,” Washington/Core, March 2004, p. 17.

Y. K. Ho, H. T. Keh and J. Ong, “The Effects of R&D and Advertising on Firm Value: An Examination of Manufacturing and Non-manufacturing Firms,” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 52, 2005, 3–14.

D. Horsky and P. Swyngedouw, “Does it Pay to Change Your Company’s Name? A Stock Market Perspective,” Marketing Science, 6 (4), 1987, 320–35.

“How Analysts View Marketing,” IPA report, July 28, 2005.

J. Huckbody, “Pierre Cardin, He’s Everywhere,” Fairfax Digital, August 1, 2003

IAS 38, International Accounting Standards Board, available at: www.iasb.org.

Indiaprwire, “Brand Licensing to be the Next Big Thing in India,” October 11, 2008. Interbrand.com.

International Bottled Water Association and the Beverage Marketing Corporation, 2008, available at: www. botteledwater.org.

International Valuation Standards Council (IVSC) Discussion, “Determination of Fair Value of Intangible Assets for IFRS Reporting Purposes Paper,” July 2007.

Investment Dealer’s Digest, “The Scramble to Brand: Not all Wall Street Banks are Equal – or Are They?” October 27, 2003.

J. Jacoby, Is it Rational to Assume Consumer Rationality? Some Consumer Psychological Perspectives on Rational Choice Theory (New York: Leonard N. Stern Graduate School of Business, 2001).

“J. D. Power Quality Study,” The Associated Press, June 4, 2008.

N. Jones and A. Hoe, “IP-backed Securitisation: Realising the Potential,” Linkelaters, 2008.

A. M. Joshi and D. M. Hanssens, “Advertising Spending and Market Capitalization,” working paper, UCLA Anderson School of Management, April 2007.

T. Kalwarski, “Investing in Brands,” BusinessWeek, July 23, 2009.

K. L. Keller, “Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-based Brand Equity,” Journal of Marketing, 57 (1), 1993, 1–22.

K. L. Keller, Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity, (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1997).

K. L. Keller, Marketing Management, 13th edn (Upper Saddle River, NJ, Prentice-Hall 2009).

K. L. Keller and D. R. Lehmann, “How, Brands Create Value?” Marketing Management, (May/June 2003) p. 23.

R. J. Kent, and C. T. Allen, “Competitive Interference Effects in Consumer Memory for Advertising: The Role of Brand Familiarity,” Journal of Marketing, 58 (3), 1994, 97–105.

J. Knowles, “Value-based Brand Measurement and Management,” Interactive Marketing, 5 (1), 2003, 40–50.

T. Koller, M. Goedhart and D.Wessels, Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies 4th edn (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

P. Kottler, A Framework for Marketing Management (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2001) p. 188.

P. Kottler, and W. Pförtsch, B2B Brand Management (Berlin: Springer, 2006).

KPMG, “Purchase Price Allocation in International Accounting,” 2007, available at: http://www.kpmg.ch/docs/Purchase_price_allocation_-_englisch_NEU.pdf.

H. Lambert, “Britons on the Prowl,” The New York Times, November 29, 1987.

P. Little, D. Coffee and R. Lirely “Brand Value and the Representational Faithfulness of Balance Sheets,” Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, September 2005.

E. F. Loftus and G. R. Loftus, “On the Permanence of Stored Information in the Human Brain,” American Psychologist, 35, 5, 409–20, 1980.

Lord Hanson, Timesonline, November 2, 2004.

“Lord of the Raiders,” The Economist, November 4, 2004.

T. Madden, F. Fehle and S. Fournier, “Brands Matter: An Empirical Investigation of Brand-building Activities and the Creation of Shareholder Value,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34 (2), 2006, 224–35.

Markenbewertung – Die Tank AG, Absatzwirtschaft, 2004.

T. McAuley, “Brand Family Values,” CFO Europe Magazine, December 31, 2003.

McKinsey “Unlock Your Financial Brand,” Marketing Practice, 2003, available at: McKinsey.com.

McKinsey “Do Fundamentals Really Drive the Stock Market?,” 2004, available at: McKinsey.com.

C. F. Mela, S. Gupta and D. R. Lehmann, “The Long-Term Impact of Advertising and Promotions on Consumer Brand Choice,” Journal of Marketing Research, 34, 1997, 248–61.

Milward Brown, Optimor, Top 100 most powerful brands 2008, available at: www.millwardbrown.com.

K. Moore, and S. Reid The Birth of Brand: 4000 Years of Branding History (McGill University, MPRA: Munich 2008) pp. 24–5.

S. Moorthy and H. Zhao “Advertising Spending and Perceived Quality,” Marketing Letters 11(3), 2000, 221–33.

Morgan Stanley, “The Relationship of Corporate Brand Strategy and Stock Price,” U.S Investment Research, June 13, 1995.

“Mother and Child Reunion: Will the AT&T/SBC Merger Build or Destroy Value?” Knowledge@Wharton, March 30, 2005.

J. Murphy (ed.), Brand Valuation (London: Hutchinson Business Books, 1989).

D. Muir, retrieved on September 16, 2009, p. 2 from: http://www.wpp.com/NR/rdonlyres/F157F2FF-BF45-409C-9737-C3550BAB15F3/0/TheStore_newsletter_006_ThePowerofBrands.pdf.

P. A. Naik, K. Raman and R. S. Winer, “Planning Marketing-Mix Strategies in the Presence of Interaction Effects,” Marketing Science, 24 (1), 2005, 25–34.

Nielson Company, The Winning Brands, retrieved from www.nielson.com. nexcen.com.

Dr. M. A. Noll, “The AT&T Brand: Any Real Value?” telecommunicationsonline, November 1, 2005.

S. Northcutt, Trademark and Brand (SANS Technology Institute, 2007). OECD.org.

Pernod Ricard, Press Release, March 31, 2008.

N. Penrose, Valuation of Trademarks, in Brand Valuation (London: Hutchinson Business Books, 1989) pp. 37–9.

R. Perrier, (ed.) Brand Valuation (London: Premier Books 1997).

M. E. Porter, Competitive Advantage (New York: Free Press, 1985).

C. Portocarrero, “Seeking Alpha,” WeSeed, February 3, 2009.

PricewaterhouseCoopers, “Markenwert wird zunehmend als Unternehmenswert anerkannt,” April 7, 2006.

PricewaterhouseCoopers “Advertising Pay Back,” 2008.

PricewaterhouseCoopers, “Kaufpreisallokation: Mehr als nur Accounting,” 2008.

J. A. Quelch, and K. E. Jocz, “Keeping a Keen Eye on Consumer Behaviour,” February 5, 2009.

J. Quelch and A. Harrington, “Samsung Electronics Company: Global Marketing Operations,” Harvard Business School, February 17, 2005.

V. R. Rao, M. K. Agarwal and D. Dahlhoff, “How Is Manifest Branding Strategy Related to the Intangible Value of a Corporation?” Journal of Marketing, 68 (4), 2004, 126–41.

E. S. Raymond, The Jargon File, December 29, 2003, see: www.catb.org/jargon/.

F. F. Reichheld, “The One Number You Need to Grow,” Harvard Business Review, e-book, March 3, 2003.

Reuters.com

M. Ritson, “Mark Ritson on Branding: BrandZ Top 100 Global Brands Shows Strength in Numbers,” Marketing Magazine April 28, 2009, available at: www.marketingmagazine.co.uk, royaltysource.com.

G. Salinas, The International Brand Valuation Manual, John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

Samsung Concludes Contract with the International Olympic Committee to Sponsor Olympic Games Through 2016, 23 April 2007, available at: Samsung.com.

S. Schwarzkopf “Turning Trade Marks into Brands: how Advertising Agencies, Created Brands in the Global Market Place, 1900–1930,” CGR Working Paper 18.

D. Shenk, Data Smog: Surviving the Information Glut (New York: HarperCollins, 1998).

S. Srinivasan and D. M. Hanssens, “Marketing and Firm Value, Metrics, Methods, Findings, and Future Directions,” Journal of Marketing Research, 46 (3), 2009.

R. E. Smith, “Integrating Information From Advertising and Trial: Processes and Effects on Consumer Response to Product Information,” Journal of Marketing Research, 30, (2), 1993, 204–19.

Sports Business Daily, September 26, 2006.

“Study Shows Brand-building Pays Off For Stockholders,” Advertising Age, 65, 1994, 18, superbrands.net.

“Top 100 Global Licensors”, Licensemag.com. April, 2009.

D. S. Tull, Van R. Wood, D. Duhan, T. Gillpatrick, K. R. Robertson and J. G. Helgeson “Leveraged Decision Making in Advertising: The Flat Maximum Principle and its Implications,” Journal of Marketing Research 23, 1986, 25–32.

D. Vakratsas and T. Ambler, “How Advertising Works, What Do We Really Know?” Journal of Marketing, 63 (1), January, 1999, 26–43.

L. Vaughan-Adams, “ICL name to vanish from tech heritage as Fujitsu rebrands,” The Independent, June 22, 2001.

D. Walker, “Building Brand Equity through Advertising,” IPSOS-ASI Research Article 5, 2002.

F. Wang, X.-P. Zhang and M. Ouyang, “Does Advertising Create Sustained Firm Value? The Capitalization of Brand Intangible,” Academy of Marketing Science, September 21, 2007.

Which, “Switching from Bottled to Tap Water, Tap vs Bottled Water,” available at: www.which.co.uk.

Woman’s Wear Daily, “Hermès’ Smart Car. . . Uniqlo’s Warm Up. . . McQ Prints It Out,” November 10, 2008.

TheWorld Customs Organization and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

T. Yeshin, Advertising, (London: Thompson Learning, 2006).

A. Zednik and A. Strebinger, “Brand Management Models of Major Consulting firms, Advertising Agencies and Market Research Companies: A Categorisation and Positioning Analysis of Models Offered in Germany, Switzerland and Austria,” Brand Management, 15 (5), 2008, 301–11.